Golden State Recorders, 665 Harrison Street, San Francisco, CA

Ad for Leo De GAr Kulka's Golded State Recorders studio • 2014 photo of current building • and gutted interior photo from several years ago

Leo De Gar Kulka (a.k.a.“The Baron”) migrated from L.A. to San Francisco in 1964 to open Golden State Recorders at 665 Harrison Street between 2nd and 3rd Streets, a gritty area at the time, now a mix of modern lofts, fancy restaurants, and the Giants’ home, AT&T Park.

The Czech-born Kulka was new to the Bay area when he first started recording bands for Autumn Records. All through the 50's and early 60's he's worked at L.A. studios-first at Radio Recorders, then at his own facility, International Recorders, where he cut tracks with such artists as Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Little Richard, Herb Albert, Sam Cooke and many others. A classic example of the “mom and pop” studio, Leo Kulka ran the studio and engineered most of the sessions. He employed a small staff, including band office manager/bookkeeper, one staff engineer, and an assistant engineer. On busier days, his wife came in to help out.

For the first few years, that small group ran one of the few music recording studios in town with a recording room comparable in size to established L.A. and New York facilities. The studio area was

at least 50×50 feet, with high ceilings, a vocal booth, and the requisite gobos to break up the square footage during a session. “At the time it was a good room; a big box, really,” George Horn describes

it bluntly. “One of the advantages of [the room’s size] was you could record a broad variety of music,” adds Vance Frost, who worked as an assistant engineer at Golden State in 1968. He returned in 1971 to serve as its lead engineer and manager until 1976. “We’d do large-scale recordings, like big bands, a few orchestral dates, and 30- to 60-voice gospel choirs.” Golden State had the size but it lacked the pristine quality of certain major market studios—which is just why a lot of clients liked it. Reflecting the no-nonsense attitude of its owner, Golden State felt lived in and unpretentious. It didn’t have much in the way of décor—no colored lights, no dimmer switches. You had two options: lights on, lights off —all or nothing. Kulka did add a few switches later so clients could at least control which lights turned on and off. He had a Neumann mastering room at Golden State as well, along with a custom 4-bus console built by staff engineer Mike Larner. Th is was later expanded to 8-bus.

A live echo chamber, accessed by walking through the electrical shop behind the control room and climbing up a ladder and through a porthole, added character—and still more reverb—to an already live room.

In addition to the handmade gear, Golden State offered an Ampex Model 200 (the first model issued by the Bay Area–based company), brought by Kulka from L.A., as well as a couple of

AG440 mono 2- and 4-track machines and at least one Ampex 350 reel-to-reel recorder. All great machines, but Kulka was slow to upgrade: When 16-track became available in the late 1960s, Golden

State hung back at four.

In its early years, Golden State, and Kulka’s engineering skills, appealed mostly to a niche of respected soul and blues artists, including Rene Hall and Wally Cox. Both of these artists already had a few decades of experience under their belts when they recorded with Kulka at Golden State. Kulka also signed some of these acts himself, either leasing sides to outside labels such as MTA and Acta or issuing singles through his Golden Soul imprint. Much of this material remained unreleased until decades later, when the public discovered his recordings from San Francisco TKOs, The Savonics,

The Spyders, Jeanette Jones, and The Generation (featuring Lydia Pense, later of Cold Blood).

The studio also attracted a few L.A.–based artists and producers and a solid cast of local musicians, such as the Beau Brummels, Sons of Champlin, Big Brother & the Holding Company, The

Charlatans, and a slew of obscure acts. Some achieved later success, while others—such as the C.A. Quintet (oddly, from Minneapolis, but they recorded their first and only album at Golden State)—

remained relatively unknown.

The same year Golden State opened its doors, the Beau Brummels recorded Introducing the Beau Brummels for Autumn Records with producers Bobby Mitchell and Sylvester Stewart

(a.k.a. the infamous Sly Stone), which included their first hit, “Laugh Laugh.”

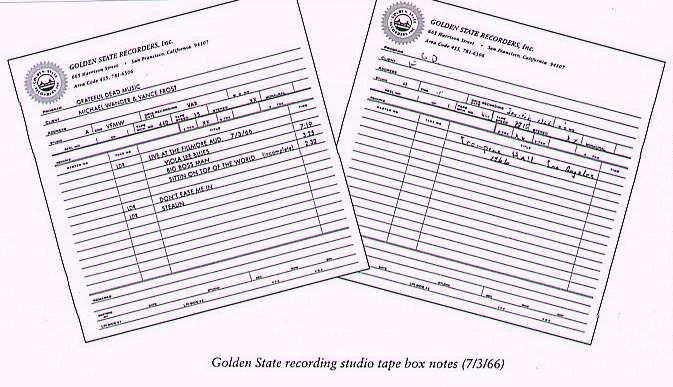

In 1965, label co-owners Tom Donahue and Mitchell brought in another one of their acts: an odd blues- and R&B-influenced rock band called The Warlocks. Half a year earlier, they had been

an anarchic acoustic group called Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions. In one day at Golden State, they recorded six songs— four originals, one traditional, and a cover of Gordon Lightfoot’s

“Early Morning Rain”—none of which were ever released until a box set 30 years later. With Kulka at the board, they recorded under the name The Emergency Crew, reportedly because bassist

Phil Lesh had spotted an album in a record store by another group called The Warlocks. Soon after, they permanently changed their name to the Grateful Dead, putting an end to any risk of band

name infringement.

They brought many other groups to Golden State to record under the Autumn Records banner, often with the help of Stewart, their secret weapon. In addition to the Beau Brummels, Stewart produced Bobby Freeman’s hit “C’mon and Swim” and other cuts for the Mojo Men, The Vejtables, and the Great Society. This last group was the launching pad for future Jefferson Airplane siren Grace Slick.

In 1969, producer Elliot Mazer came by to finish a portion of Nick Gravenites’ album, My Labors, at Golden State. Much of the album came from the same sessions that produced Live at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West by Michael Bloomfield (recorded with Kulka’s remote truck).

Business began to slow at Golden State in the early 1970s as other facilities made their way into the city. The most notable of these was Wally Heider Recording. Musicians, fickle as they can be,

wanted to record at the “in” studios with the “in” equipment, which put a dent in Golden State’s business.

Leo loved to experiment with new recording techniques, but he was a traditionalist at heart. He used a “back to basics” approach with his students. To the end, Leo waxed ecstatic over his Ampex model 200 (the first tape recorder produced in this country). And he may have been the last living audio engineer to edit tape without a splicing block or a razor blade. He’d lay a section of tape across his left hand, precisely lining it up with his thumb and finger, and using a small scissors, he made fast splices that always joined perfectly.

Source -