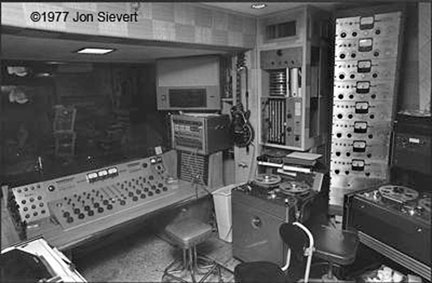

Ampex Sel-Sync, 1955

Oct 1, 2005 , By George Petersen

Mix Magazine

WHEN THE ROOTS OF MULTITRACK TOOK HOLD

There's no doubt that the impetus for multitracking came from solid-body electric guitar inventor Les Paul, who, lacking a means to play harmony parts and duets with himself, modified a tape deck with an extra head and a switch to defeat the erase function and began doing sound-on-sound recording as early as 1949. However, the technique was risky: One bad pass and the recording was ruined, and each additional pass added noise and distortion.

“The 8-track [concept] came along in 1953,” Paul recalls. “While filming, I was taking a rest and looking up at the sky. My manager asked what I was dreaming about. I said that recording using sound-on-sound was crazy. There's a better way: Stack the heads on top of the other — 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8 — and align them so we could do self-sync with all the heads in-line. When I told my manager, ‘I think it will change the world,’ he told me I should do something about it.

Les Paul (holding a Fostex cassette multitrack) poses with his original Ampex 8-track, which was given the name “Octopus” by comedian W.C. Fields.

“I went to California to see Westrex, who said it wouldn't work,” he continues. “So we went up to San Francisco to see Ampex. They called a big meeting and they said they could do it. All we have to do is hire about seven people to start the procedure, which was in 1953. It took about two years, during which they also made a number of refinements, such as a master oscillator and remoting it to the console.”

However the process wasn't so easy, according to Ross Snyder, Ampex manager of special products from 1952 to 1960. These days, this distinguished AES Fellow is retired and often produces oral history recordings for the AES history committee, but back then, Snyder's domain was “custom shop” — type products for the company.

Snyder also developed the concept for Sel-Sync. “I was alone in my office at 860 Charter Street in Redwood City [Calif.] and thinking about how godawful sound-on-sound recordings became after 15 or 16 layers down,” Snyder says. “You exaggerate the frequency response, you bring up the hum and noise, you increase the distortion — the whole thing is just a mess. There were many people doing those things, not just Les Paul, although Les was perhaps the best at doing it.”

Snyder also developed the concept for Sel-Sync. “I was alone in my office at 860 Charter Street in Redwood City [Calif.] and thinking about how godawful sound-on-sound recordings became after 15 or 16 layers down,” Snyder says. “You exaggerate the frequency response, you bring up the hum and noise, you increase the distortion — the whole thing is just a mess. There were many people doing those things, not just Les Paul, although Les was perhaps the best at doing it.”

The Sel-Sync process that enabled overdub multitracking required several systems to function as one. “There was nothing new about the idea that a record head could function perfectly well — or rather well — as a pickup head,” Snyder adds. “But to do that job you needed to get them in perfect alignment, so that when you played back, you were in synchronism. You needed a separate erase so you could preserve what was already recorded and use a new track for the next pass. But to get them in synchronism, you also had to solve the problem of switching very low-level/high-impedance circuitry. You've got to handle those things very carefully with considerable skill to avoid noise and hum.

“The whole thing did not look to me as though it were possible, but I inquired with the engineers in the mod lab, and one by one — especially one very bright, delightful person by the name of Mort Fujii — said, ‘We could do that.’” The first Sel-Sync machine was the 1-inch 8-track sold to Paul for $10,000 — a princely sum that could have bought two nice homes back in 1955. The system combined a separate rack of record electronics with a heavy-duty instrumentation recorder transport, the latter chosen because it was proven to pull 1-inch tape, which led to some later complications.

“They sent me a 30/60 ips machine!” Paul exclaims. “We set the thing up and Mary [Ford] asked, ‘Isn't that thing going awfully fast?’ I wasn't sure, so I stuck a piece of paper into the tape pack and counted off to verify the speed.” Sure enough, the Ampex team — who had never built a 1-inch multitrack — didn't remove the instrumentation capstan, so the deck ran at 30/60 ips instead of 15/30, and as the electronics were compensated for the higher speeds, the entire system was air-freighted back to Ampex and then returned to Paul's studio in New Jersey, where it still continues to work. “I'm sure we lost money on that,” Snyder recalls.

Ironically, Ampex hardly made a fuss about the new technology. “It was partly because of me,” Snyder explains. “I did not consider it an important or major new feature. I thought the market would be confined to a few dozen at the absolute most. After all, how many people are doing professional recording by way of overdubbing? Not many, but those who did needed it badly. Also, our attorney advised me that the concept was ‘obvious’ engineering and probably not patentable. The only thing Ampex ever did with it was trademark the [Sel-Sync] name.”

Snyder does have one lament: “I often wished that Les would have made a greater success with the machine; he never had a hit again. By 1955/'56/'57, when Les was using the new machine, rock 'n' roll had taken over and he was not a rock artist. I would like to say we made five or six of his hits possible, but that wouldn't be true — they were all done earlier using sound-on-sound.”

So 50 years later, how does the “father of multitracking” feel about his impact on music? “I'm terribly proud, but I'm very humble about it,” says Paul. “If it wasn't for Bell Labs, I wouldn't have been singing into their telephone, and if there wasn't an Edison, there wouldn't be a phonograph. If I didn't have those things to play with, like the telephone receiver I put underneath the strings of my guitar and plugged into the grid of my mother's radio, it wouldn't have happened. I was just lucky enough to have others that had done so much who deserve so much credit.”