UK Gramophone Company

The UK Gramophone Company was founded by William Barry Owen and his partner/investor Trevor Williams in 1897 as the UK partner of Emile Berliner's United States based United States Gramophone Company, which had been founded in 1892. In December 1900, William Owen gained the manufacturing rights for the Lambert Typewriter Company and The Gramophone Company was for a few years renamed to the Gramophone & Typewriter Ltd.

The Gramophone Co. trademark (right) on early single sided British Gramophone records.

In 1900, the United States branch of Gramophone lost a patent infringement suit, brought on by Columbia Records and Zonophone, and was no longer permitted to produce records in the USA. Gramophone's talking machine manufacturer, Eldridge R. Johnson, being left with a large factory and thousands of talking machines with no records to play on  them, filed suit that year to be permitted to make records himself, and won, in spite of the negative verdict against Berliner.

them, filed suit that year to be permitted to make records himself, and won, in spite of the negative verdict against Berliner.

An early Gramophone Co. record label (right) showing the original Trademark

This victory by Johnson, which would be used in naming the new record company the Victor Talking Machine Company he would found the following year, may have been in part due to a patent-pooling handshake agreement with Columbia that allowed the latter to begin producing flat records themselves, which they began doing in 1901, (all Columbia records had previously been cylinders). Contrary to some sources, the Victor Talking Machine Company was never a branch or subsidiary of Gramophone, as Johnson's manufactory, which had been making talking machines for Berliner, was his own company with many mechanical patents that he owned, which patents were valuable in the patent pool agreement with Columbia. Thus, Victor and Columbia began making flat records in America, with UK Gramophone and others continuing to do so outside America, leaving Edison as the only major player in the making of cylinders (Columbia still made a limited number for a few years), and Emile  Berliner, the inventor of flat records, out of the business. All he was left with were the master recordings of his earlier records, which he took to Canada and reformed his Berliner label in Montreal, Nipper logo and all. Edison would soon join the flat record market with his diamond discs and their players.

Berliner, the inventor of flat records, out of the business. All he was left with were the master recordings of his earlier records, which he took to Canada and reformed his Berliner label in Montreal, Nipper logo and all. Edison would soon join the flat record market with his diamond discs and their players.

An early Gramophone Co. record label showing the HMV Trademark

A public relations triumph of 1907 involved Alfred Clark, a New York representative of the company. Clark encouraged the Paris Opera to seal and lock 24 records in two iron and lead containers in a basement storage room at the opera. These were to be opened in 100 years. 24 more records were added to the first group in two additional containers in 1912, along with a hand-crank gramophone with spare stylus needles to insure the records could be played when unsealed. In 1989, it was discovered that one of the 1912 containers had been opened and emptied and the gramophone stolen. The three remaining containers were moved to the French National Library. When opened in December 2007, some of the records were broken but copies of all the missing and broken records were located in the French National Library. EMI digitized the collection and released it on three compact discs in February 2009 as “Les Urnes de l'Opera”.

In February 1909,  the company introduced new labels featuring the famous trademark known as "His Master's Voice", generally referred to as HMV, todistinguish them from earlier labels which featured an outline of the Recording Angel trademark. The latter had been designed by Theodore Birnbaum, an executive of the Gramophone Company pressing plant in Hanover, Germany. The Gramophone Company was never known as the HMV or His Master's Voice company. An icon of the company was to become very well known - the picture of a dog listening to an early gramophone painted in England by Francis Barraud (right). The painting "His Master's Voice" was made in the 1890s with the dog listening to an Edison cylinder Phonograph, which was capable of recording as well as playing, but Thomas Edison did not buy the painting.

the company introduced new labels featuring the famous trademark known as "His Master's Voice", generally referred to as HMV, todistinguish them from earlier labels which featured an outline of the Recording Angel trademark. The latter had been designed by Theodore Birnbaum, an executive of the Gramophone Company pressing plant in Hanover, Germany. The Gramophone Company was never known as the HMV or His Master's Voice company. An icon of the company was to become very well known - the picture of a dog listening to an early gramophone painted in England by Francis Barraud (right). The painting "His Master's Voice" was made in the 1890s with the dog listening to an Edison cylinder Phonograph, which was capable of recording as well as playing, but Thomas Edison did not buy the painting.

In 1899, Owen bought the painting from the artist, and asked him to paint over the Edison machine with a Gramophone, which he did. Technically, since Gramophones did not record, the new version of the painting makes no sense, as the dog would not have been able to listen to his master's voice (the master being Barraud's deceased brother). In 1902, Eldridge Johnson of Victor Talking Machine Company acquired US rights to use it as the Victor trademark, which began appearing on Victor records that year. UK rights to the logo were reserved by Gramophone. Nipper lived from 1884 to 1895 and is buried in England with a celebrated grave marker.

In March 1931 The Gramophone Company merged with Columbia Graphophone Company to form Electric and Musical Industries Ltd (EMI). The "Gramophone Company, Ltd." name, however, continued to be used for many decades, especially for copyright notices on records. Gramophone Company of India was formed in 1946. The Gramophone Company Ltd legal entity was renamed EMI Records Ltd in 1973.

Electric and Musical Industries Ltd

Electric and Musical Industries Ltd was formed in March 1931 by the merger of the Columbia Graphophone Company and the Gramophone Company, with its "His Master's Voice" record label, firms that have a history extending back to the origins of recorded sound. The new vertically integrated company produced sound recordings as well as recording and playback equipment.

Manufacturing

The company's gramophone manufacturing led to forty years of success with larger-scale electronics and electrical engineering. Alan Blumlein, a skilled engineer employed by EMI, conducted a great deal of pioneering research into stereo sound recording, however many years prior to the perfection of the medium in the early '50s, he was killed in 1942 whilst conducting trials on an experimental H2S radar unit.

During and after the Second World War, the EMI Laboratories in Hayes, Hillingdon developed radar equipment and guided missiles, employing analogue computers.

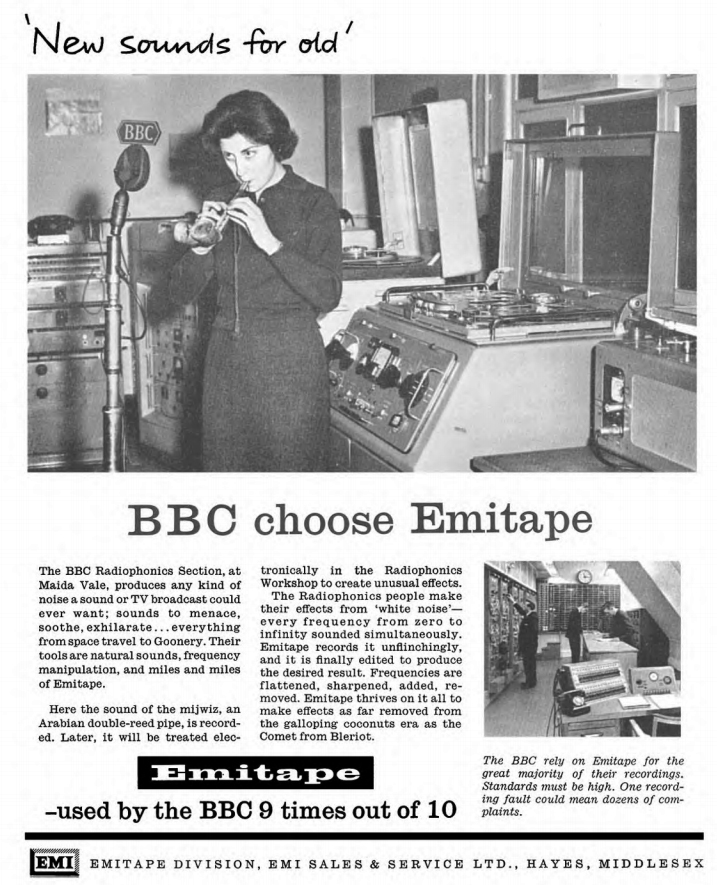

British Tape Recorders or BTR

The BBC acquired some Magnetophone machines (left) in 1946 on an experimental basis, and these were used in the early stages of the new Third Programme to record and playback performances of operas from Germany (live relays being problematic because of the unreliability of the land lines in the immediate post-war period). The tapes ran at 30 inches/second (ips), and the flexible base provided much better contact with the head: the main reason for the improvement in the sound was the addition of a high-frequency current at 100kHz to the audio signal, which avoided the inherent distortion in the magnetization process.

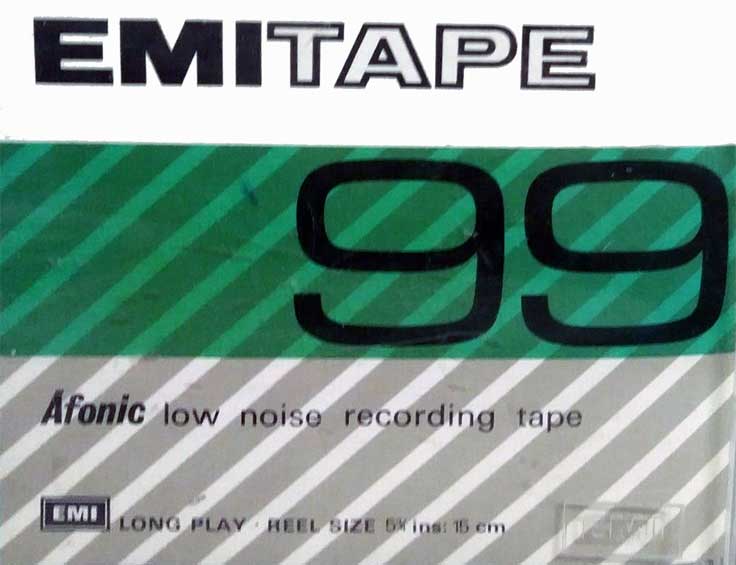

These machines were used until 1952, though most of the work continued to be done using the established media; but from 1948 a new British model became available from EMI: the BTR1. Though in many ways clumsy, its quality was good, and as it wasn't possible to obtain any more Magnetophones it was an obvious choice. There was some difficulty with the tape: early EMI tape was very prone to print-through (where the magnetic image on one layer causes the next layer on the spool to pick up a faint version, causing pre- and post-echoes, often through several layers)

These machines were used until 1952, though most of the work continued to be done using the established media; but from 1948 a new British model became available from EMI: the BTR1. Though in many ways clumsy, its quality was good, and as it wasn't possible to obtain any more Magnetophones it was an obvious choice. There was some difficulty with the tape: early EMI tape was very prone to print-through (where the magnetic image on one layer causes the next layer on the spool to pick up a faint version, causing pre- and post-echoes, often through several layers)

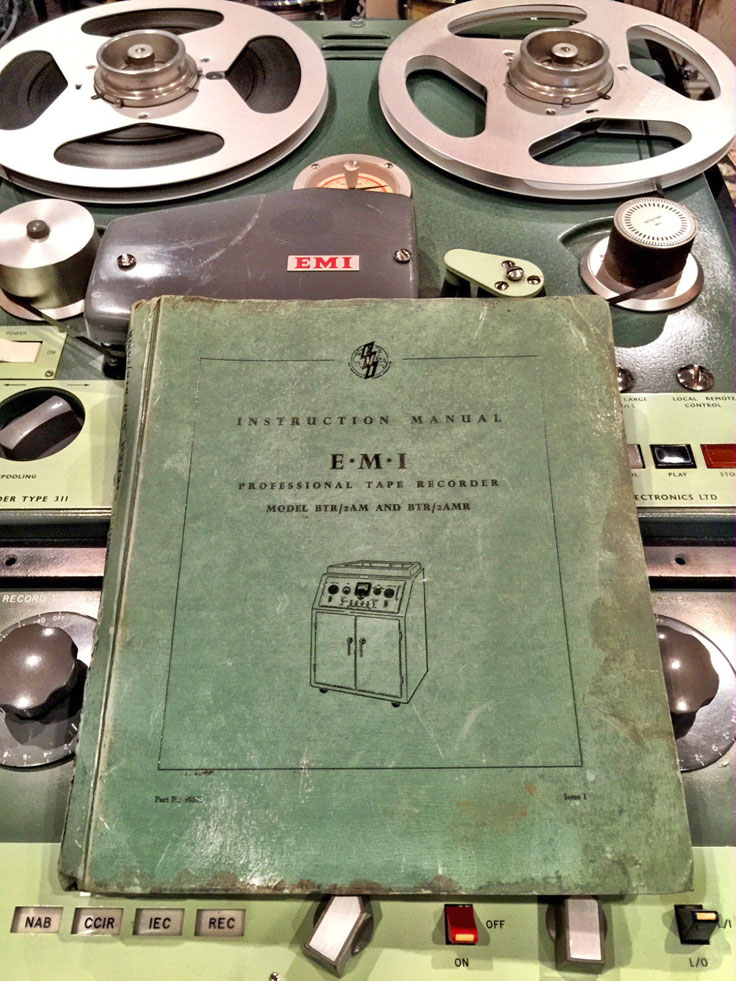

British Tape Recorders or BTR machines were reel-to-reel tape recorders initially made by EMI in England after World War II. They were the first magnetic tape recorders to be manufactured in Britain, and their design imitated that of the tape recorders used by the Germans during the war. Because these multi-track recorders were painted EMI green, they then became known as the "Green Machines".

The first model made was named the BTR1. The BTR1 machines were first created in 1947, but superseded by the BTR2 mono machine in 1952 (with bias current, giving them better fidelity). The BTR2 was made in greater quantity, being used not only at EMI studios but at the BBC. Many studios later purchased ex-BBC units, so quite a few were found in non-EMI London studios. The BTR3 (right) recorder was initially intended to support 2 or 4 tracks, but the only machines produced were the stereo (2-track) machines, the 4-track version having been rejected at the

The first model made was named the BTR1. The BTR1 machines were first created in 1947, but superseded by the BTR2 mono machine in 1952 (with bias current, giving them better fidelity). The BTR2 was made in greater quantity, being used not only at EMI studios but at the BBC. Many studios later purchased ex-BBC units, so quite a few were found in non-EMI London studios. The BTR3 (right) recorder was initially intended to support 2 or 4 tracks, but the only machines produced were the stereo (2-track) machines, the 4-track version having been rejected at the prototype stage. Only a few of these BTR3s were built, and the only known use of them is at the famous Abbey Road studios during the 1960s, where they were used for all stereo recording and disc mastering.

prototype stage. Only a few of these BTR3s were built, and the only known use of them is at the famous Abbey Road studios during the 1960s, where they were used for all stereo recording and disc mastering.

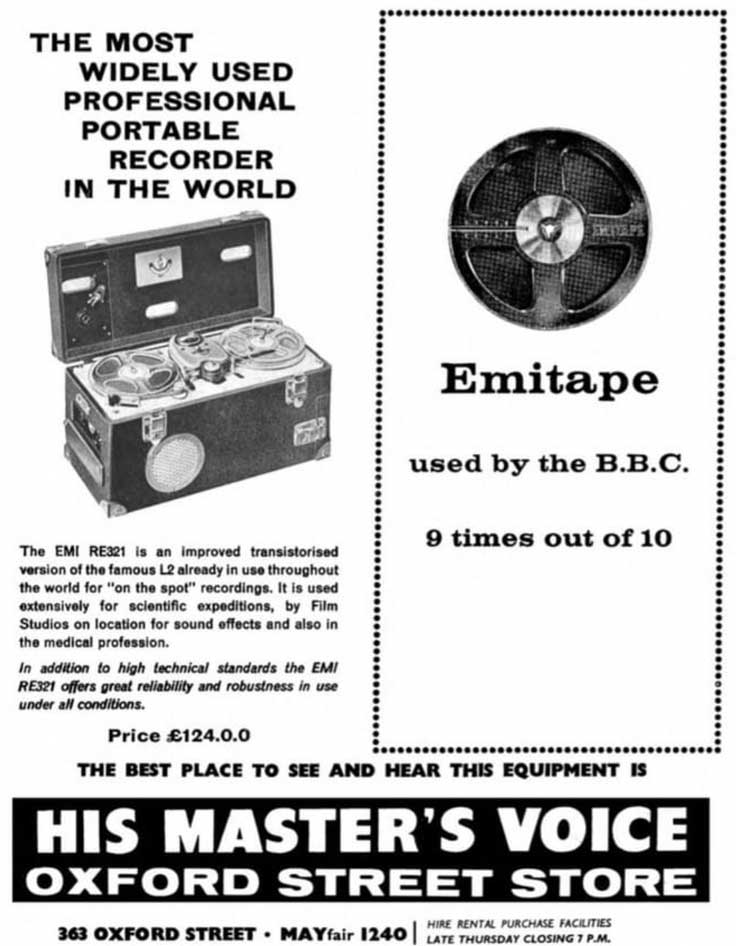

The TR90 was a smaller and more portable stereo unit, and used professionally on EMI Remote recordings, as well as at Hayes, EMI's manufacturing complex.

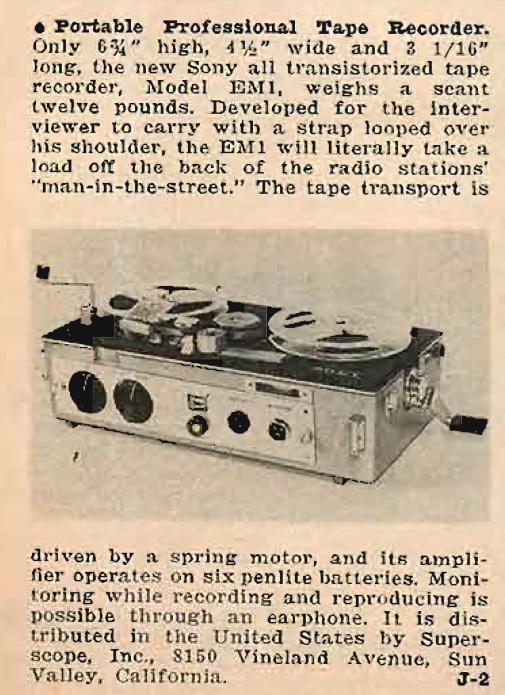

Interestingly in 1961 Sony built a professional portable tape recorder and named it the EMI (rt)

The Otari company made a BTR-5 model recording machine, the initials standing for Broadcast Tape Recorder.

Mono and twin-track BTR reel-to-reel recording machines were used in the making of the first two Beatles albums. Mono and stereo BTR machines were used to mix down the 4 and 8 track masters of later albums recorded on Telefunken, Studer and 3M multi-track machines.

down the 4 and 8 track masters of later albums recorded on Telefunken, Studer and 3M multi-track machines.

The company later became involved in broadcasting equipment, notably providing the first television transmitter to the BBC. It also manufactured broadcast television cameras for British television production companies, for the BBC, and the commercial television ITV companies used them as well alongside cameras made by Pye and Marconi. Their best remembered piece of broadcast television equipment was the EMI 2001 color television camera, which became the mainstay of much of the British television industry from the end of the 1960s until the early 1980s. Exports of this piece of equipment were low however, and EMI left this area of product manufacture.

The company later became involved in broadcasting equipment, notably providing the first television transmitter to the BBC. It also manufactured broadcast television cameras for British television production companies, for the BBC, and the commercial television ITV companies used them as well alongside cameras made by Pye and Marconi. Their best remembered piece of broadcast television equipment was the EMI 2001 color television camera, which became the mainstay of much of the British television industry from the end of the 1960s until the early 1980s. Exports of this piece of equipment were low however, and EMI left this area of product manufacture.

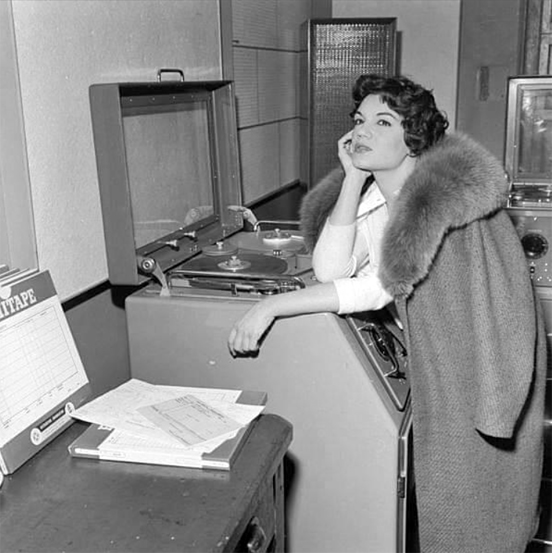

Following an idea from her father, Connie Francis (left with EMI recorder) traveled to London in August 1959 to record an Italian album at EMI's famous Abbey Road Studios

In 1958 the EMIDEC 1100, the UK's first transistorized computer, was developed at Hayes under the leadership of Godfrey Hounsfield. In the early 1970s, Hounsfield developed the first CAT scanner, a device which revolutionized medical imaging. In 1973 EMI was awarded a prestigious Queen's Award for Technological Innovation for what was then called the EMI scanner, and in 1979 Hounsfield won the Nobel Prize for his accomplishment. After brief, but brilliant, success in the medical imaging field, EMI's manufacturing activities were sold off to other companies, notably Thorn (see Thorn EMI). Subsequently development and manufacturing activities were sold off to other companies and work moved to other towns such as Crawley and Wells.

Emihus Electronics, based in Glenrothes, Scotland, was owned 51% by Hughes Aircraft, of California, U.S., and 49% by EMI. It manufactured integrated circuits and, for a short period in the mid-1970s, made hand-held calculators under the Gemini name.

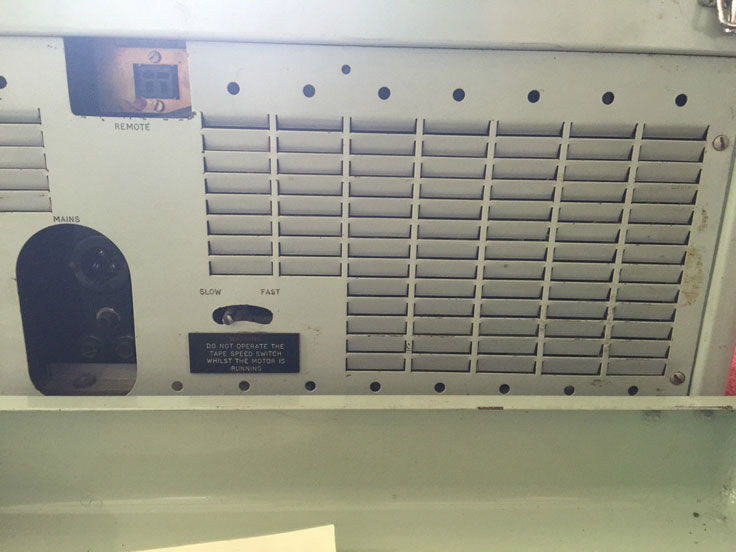

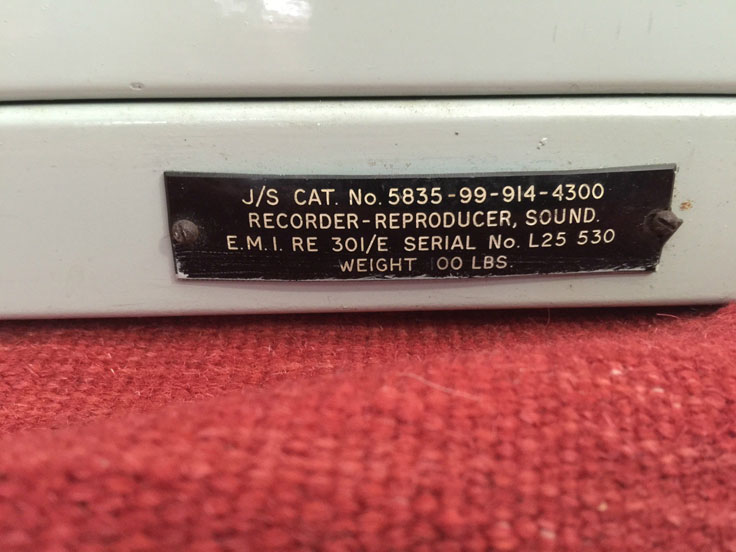

EMI Professional Tape Recorders - Photos with permission from Danny White

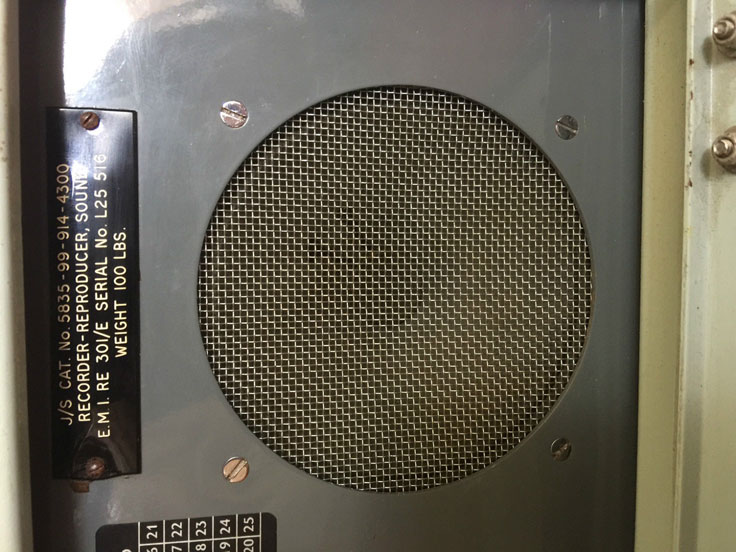

"EMI RE 301/E. Super rare EMI tube 1/4" stereo tape machine. Really nice shape and well taken care of. The way I understand it is this is the military version of the EMI TR 52. The only paperwork I got with it stated that it was tested for playback in 2001 and was working. Very heavy and built like a tank. Overall, I would say it's about as good of condition as could be found fifty one years on. EMI made these in 1965." - Danny White (this recorder is not for sale on our site)

"EMI BTR 4 tube, analog reel to reel tape machine. From recent purchase of private collection in England. The EMI BTR 4 is a Mono 1/4" tape machine. The history of EMI recorders is a storied one in that the BTR (BTR-2) Series was used for the early recordings of The Beatles. These machines were built to very high and exacting standards and were intended to last a lifetime. I believe this machine to be from the early to mid 1960's and is in fantastic condition. These machines are super rare and were made in very small quantities as they were extremely expensive for their day. The EMI tube microphone preamp in this machine alone, is highly sought after as is most anything made by EMI due the the high build quality." - Danny White (this recorder is not for sale on our site)

Music

Early in its life, the Gramophone Company established subsidiary operations in a number of other countries in the BritishCommonwealth, including India, Australia and New Zealand. Gramophone's (later EMI's) Australian and New Zealand subsidiaries dominated the popular music industries in those countries from the 1920s until the 1960s, when other locally owned labels (such as Festival Records) began to challenge the near monopoly of EMI. Over 150,000 78-rpm recordings from around the world are held in EMI's temperature-controlled archive in Hayes, some of which have been released on CD since 2008 by Honest Jon's Records.

Early in its life, the Gramophone Company established subsidiary operations in a number of other countries in the BritishCommonwealth, including India, Australia and New Zealand. Gramophone's (later EMI's) Australian and New Zealand subsidiaries dominated the popular music industries in those countries from the 1920s until the 1960s, when other locally owned labels (such as Festival Records) began to challenge the near monopoly of EMI. Over 150,000 78-rpm recordings from around the world are held in EMI's temperature-controlled archive in Hayes, some of which have been released on CD since 2008 by Honest Jon's Records.

In 1931, the year the company was formed, it opened the legendary recording studios at Abbey Road, London. During the 1930s and 1940s, its roster of artists included Arturo Toscanini, Sir Edward Elgar, and Otto Klemperer, among many others. During this time EMI appointed its first A&R managers. These included George Martin, who later brought the Beatles into the EMI fold.

When the Gramophone Company merged with the Columbia Graphophone Company (including Columbia's subsidiary label Parlophone) in 1931, the new Anglo-American group was incorporated as Electric & Musical Industries Ltd. At this point RCA had a majority shareholder in the new company, giving RCA chair David Sarnoff a seat on the EMI board.

However, EMI was subsequently forced to sell Columbia USA due to anti-trust action taken by its American competitors. By this time the record industry had been hit hard by the Depression and in 1934 a much-diminished Columbia USA was purchased for just US$70,500 by ARC-BRC (American Record Corporation–Brunswick Record Company), which also acquired the OKeh label.

RCA sold its stake in EMI in 1935, but due to its earlier takeover of the Victor label in 1929, RCA retained the North and South American rights to the "Nipper" trademark. In other countries, the Dog and Phonograph Logo was used by the EMI subsidiary label HMV, even though the slogan itself would be retained by RCA along with the logo.

In 1938 ARC-Brunswick was taken over by CBS, which then sold the American Brunswick label to American Decca Records, which along with its' other properties, Aeolian Records and Vocalion Records, used it as a subsidiary budget label afterward. CBS then operated Columbia as its flagship label in both the United States and Canada.

However. to make it even more confusing, EMI retained the rights to the Columbia name in most other territories including the UK, Australia and New Zealand. It continued to operate the label with moderate success until 1972, when it was retired and replaced by the EMI Records imprint, so if you see any Columbia Records manufactured outside North America between 1972 and 1992, they are rare indeed.

In 1990, following a series of major takeovers that saw CBS Records acquired by the Sony Corporation of Japan, EMI sold its remaining rights to the Columbia name to Sony and the label is now operated exclusively throughout the world by Sony Music Entertainment; except in Japan where the trade mark is owned by Columbia Music Entertainment,

EMI released its first LPs in 1952 and its first stereophonic recordings in 1955 (first on reel-to-reel tape and then LPs, beginning in 1958). In 1957, to replace the loss of its long-established licensing arrangements with RCA Victor and Columbia Records (Columbia USA cut its ties with EMI in 1951) and EMI entered the American market by acquiring 96% of the stock for Capitol Records USA.

From 1960 to 1995 their "EMI House," corporate headquarters was located at 20 Manchester Square London, England, the stairwell from which was featured on the cover of the Beatles' Please Please Me album. In addition, an unused shot from the Please Please Me photo session featuring the boys in short hair and clean cut attire, was used for the cover of the Beatles' first double-disc greatest-hits compilation entitled 1962–1966 (aka "The Red Album"). In 1969, Angus McBean took a matching group photograph featuring the boys in long hair and beards to contrast with the earlier clean cut image in order to show that the boys could have appeal across a wide range of audiences. This photo was originally intended for the Get Back album which later was entitled Let It Be. The photo was used instead for the cover of the Beatles second greatest-hits double-disc compilation entitled 1967–1970 (aka "The Blue Album"). (The two compilations were released in 1973.)

From 1960 to 1995 their "EMI House," corporate headquarters was located at 20 Manchester Square London, England, the stairwell from which was featured on the cover of the Beatles' Please Please Me album. In addition, an unused shot from the Please Please Me photo session featuring the boys in short hair and clean cut attire, was used for the cover of the Beatles' first double-disc greatest-hits compilation entitled 1962–1966 (aka "The Red Album"). In 1969, Angus McBean took a matching group photograph featuring the boys in long hair and beards to contrast with the earlier clean cut image in order to show that the boys could have appeal across a wide range of audiences. This photo was originally intended for the Get Back album which later was entitled Let It Be. The photo was used instead for the cover of the Beatles second greatest-hits double-disc compilation entitled 1967–1970 (aka "The Blue Album"). (The two compilations were released in 1973.)

EMI's classical artists of the period were largely limited to the prestigious British orchestras, such as the Philharmonia Orchestra and London Symphony Orchestra. During the era of the long-playing record (LP), very few U.S. orchestras had their principal recording contracts with EMI, one notable exception being that of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, especially during the tenure of William Steinberg.

From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, the company enjoyed huge success in the popular music field under the management of Sir Joseph Lockwood. The strong  combination of EMI and its subsidiary labels (including Parlophone, HMV, Columbia and Capitol Records) along with a r

combination of EMI and its subsidiary labels (including Parlophone, HMV, Columbia and Capitol Records) along with a r oster of stellar groups such as The Hollies, The Shadows, The Beach Boys, and The Beatles along with hit solo performers such as Frank Sinatra, Cliff Richard, and Nat 'King' Cole, made EMI the best-known and most successful recording company in the world at that time.

oster of stellar groups such as The Hollies, The Shadows, The Beach Boys, and The Beatles along with hit solo performers such as Frank Sinatra, Cliff Richard, and Nat 'King' Cole, made EMI the best-known and most successful recording company in the world at that time.

In 1967, while shifting their pop and rock music roster to Columbia, EMI converted HMV solely to a classical music label exclusively. For the emerging progressive rock genre including Pink Floyd, who had debuted on Columbia, EMI established a new subsidiary label, Harvest Records two years later.

In 1971, Electric & Musical Industries changed its name to EMI Ltd. and a year later EMI replaced the Columbia label with the EMI Records imprint. Two years later, the Gramophone Company subsidiary became EMI Records Ltd as well, and in February 1979, EMI Ltd acquired United Artists Records and with it their subsidiary labels Liberty Records and Imperial Records.

Eight months later, THORN Electrical Industries merged with EMI Ltd. to form Thorn EMI.

Ten years later in 1989, Thorn EMI bought a 50% interest in Chrysalis Records, completing the buyout two years later. Six months after completing the buyout of Chrysalis, Thorn EMI bought Virgin Records from Richard Branson in one of its highest-profile and most expensive acquisitions in record music history.

Aftermath of demerger from Thorn

Due to the increasing divergence of business models, Thorn EMI shareholders voted in favour of demerger proposals on 16 August 1996. The resulting media company was now known as EMI Group PLC.

Since the 1930s, the Baak Doi label headquartered in Shanghai had been published under the EMI banner and since then, EMI had also been the dominant label in the cantopop market in Hong Kong until the genre's decline in the mid 1980s. Between the years 2004–2006, EMI then completely and totally divested itself from the c-pop market, and after that, all Hong Kong music artists previously associated with EMI have had their music published by Gold Label, a concern unaffiliated with EMI and with which EMI does not hold any interest.

On 21 November 2000, Streamwaves and EMI signed a deal licensing EMI's catalogue in a digital format for their online streaming music service. This was the first time EMI had licensed any of its catalogue to a streaming music website.

Pop star Robbie Williams signed a 6 album deal in 2002 paying him over £80 million ($157 million), which was not only the biggest recording contract in British music history at the time, but also the second biggest in music history behind that of Michael Jackson.

Apple Records, the record label representing the The Beatles, launched a suit against EMI for non-payment of royalties on 15 December 2005. The suit alleged that EMI have withheld $50 million from the record label, however an EMI spokesman noted that audits of record label accounts are not that unusual, confirming at least two hundred such audits performed on the label, but that these audits rarely result in legal action. A legal settlement was announced on 12 April 2007 and terms were undisclosed.

On 2 April 2007, EMI announced it would begin releasing its music in DRM-free formats. Initially they are rolling out in superior sounding high-bitrate AAC format via Apple's iTunes Store (under the iTunes Plus category).

Tracks will cost $1.29/€1.29/£0.99. Legacy tracks with FairPlay DRM will still be available for $0.99/€0.99/£0.79 – albeit with lower quality sound and DRM restrictions still in place. Users will be able to ‘upgrade’ the EMI tracks that they have already bought for $0.30/€0.30/£0.20. Albums are also available at the same price as their lower quality, DRM counterparts and music videos from EMI will also be DRM-free. The higher-quality, DRM-free files became available worldwide on iTunes on 30 May 2007, and are expected to appear on other music download services as well in the near future.

Since then Universal Music Group has also announced sales of DRM-free music (which they described as an experiment).

In May 2006, EMI attempted to buy Warner Music Group, which would have reduced the world's four largest record companies (Big Four) to three; however, the bid was rejected. Warner Music Group launched a Pac-Man defence, offering to buy EMI. EMI rejected the $4.6bn offer.

Terra Firma takeover

After a dramatic 7% decline in the British market share, from 16% to 9% and the announcement that EMI had sustained a loss of £260 million in 2006/2007, EMI was  acquired by Terra Firma Capital Partners in August 2007 which purchased it for £4.2 billion.

acquired by Terra Firma Capital Partners in August 2007 which purchased it for £4.2 billion.

Following the transition, several important artists including Radiohead walked away from the label, while other artists such as Paul McCartney had seen the writing on the wall and left ahead of the takeover. At the same time, The Rolling Stones signed a one-album deal with Interscope Records/Universal Music Group outside of its contract with EMI, which expired on February 2008, and then in July 2008 signed a new long term deal with Universal Music Group.

The Terra Firma takeover is also reported to have been the catalyst behind a lawsuit filed by Pink Floyd over unpaid royalties. In January 2011 Pink Floyd signed a new global agreement with EMI.

Around the same time, Guy Hands, CEO of Terra Firma Capital Partners, came to EMI with restructuring plans to cut between 1,500 and 2,000 jobs and to reduce costs by £200 million a year. As a result, the UK chief executive Tony Wadsworth left EMI after 25 years in January 2008. The cuts were planned to take effect over the year 2008, and will affect up to a third of EMI's 5,500 staff. Another EMI singer Joss Stone battled the label, and has offered to forfeit £2 million ($2.8 million) in hopes of being released from her contract. Stone has said that after EMI was taken over by Terra Firma, her relationship with the label has gone sour and that there is "no working relationship". In an interview with BBC 6music, Róisín Murphy clearly stated that she left the label as well because of similar disagreements. She also commented on the difficulties she had while recording her second solo album Overpowered.

In 2008, EMI withdrew from the South-East Asian market entirely, forcing its large roster of acts to search out contracts with other unaffiliated labels. As a result, the South-East Asian market is now the only region in the world where EMI is no longer in operation, although the record label does continue to operate in Hong Kong and Indonesia (which is currently named Arka Music Indonesia). The Chinese and Taiwanese operation of EMI as well as the Hong Kong branch of Gold Label, was sold to Typhoon Group and reformed as Gold Typhoon. The Philippine branch of EMI changed its name to PolyEast Records, and is now a joint venture between EMI itself and Pied Piper Records Corporation. The physical audio and video products of the label have been distributed in South-East Asia by Warner Music since December 2008, while new EMI releases in China and Taiwan, were distributed under Gold Typhoon which was previously known as EMI Music China and EMI Music Taiwan, respectively. Meanwhile, the Korean branch of EMI (known as EMI Korea Limited) had its physical releases distributed by Warner Music Korea. EMI Music Japan, the Japanese EMI branch, remains unchanged from the reflection of Toshiba's divestiture to the business by EMI buying the whole branch way back July 2007, making it a full subsidiary.

In July 2009, there were reports that EMI would not sell CDs to independent album retailers in a bid to cut costs, but in fact only a handful of small physical retailers were affected.

Citigroup ownership

In February 2010, EMI Group reported pre-tax losses of £1.75 billion for the year ended March 2009, including write-downs on the value of its music catalogue. In addition, KPMG issued a going concern warning on the holding company's accounts regarding an ability to remain solvent.

Citigroup (which held $4 billion in debt) took 100% ownership of EMI Group from Terra Firma Capital Partners on 1 February 2011, writing off £2.2 billion of debt and reducing EMI's debt load by 65%. The group was put up for sale and final bids were due by 5 October 2011.

Sony/Universal sale

On 12 November 2011, it was announced that EMI would sell its recorded music operations to Universal Music Group for £1.2 billion ($1.9 billion) and its music  publishing operations to Sony/ATV Music Publishing-for $2.2 billion. Among the other companies that had competed for the recorded music business was Warner Music Group which was reported to have made a $2 billion bid. However, IMPALA has said that it would fight the merger. In March 2012, the European Union opened an investigation into Universal's purchase of EMI's recorded music division and had asked rivals and consumer groups whether the deal will result in higher prices and shut out competitors.

publishing operations to Sony/ATV Music Publishing-for $2.2 billion. Among the other companies that had competed for the recorded music business was Warner Music Group which was reported to have made a $2 billion bid. However, IMPALA has said that it would fight the merger. In March 2012, the European Union opened an investigation into Universal's purchase of EMI's recorded music division and had asked rivals and consumer groups whether the deal will result in higher prices and shut out competitors.

On 21 September 2012, the sale of EMI to UMG was approved in both Europe and the United States by the European Commission and the Federal Trade Commission respectively. The European Commission approved the deal, however, under the condition that the merged company divest itself of one third of its total operations to other companies with a proven track record in the music industry. To comply with this condition, UMG plans to divest itself of EMI Records, Parlophone Records, Sanctuary Records, Chrysalis Records, Mute Records, EMI Classics, Virgin Classics, and EMI's regional labels across Europe. The merged company will, however, retain its ownership of the Beatles' library (Parlophone) and Robbie Williams' Chrysalis recordings.

Universal Music Group completed its acquisition of EMI on 28 September 2012. In compliance the conditions of the European Commission, Universal Music Group sold a German-based music rights company BMG the Mute catalogue, previously property of EMI on December 22, 2012. On February 8 2013, Warner Music Group is made to control of Parlophone Records, Chrysalis Records, EMI Classics, Virgin Classics and EMI's regional labels across Europe, pending the approval of both European and American regulators, to a value of $765 million (£487 million).

EMI Music Publishing

As well as the well-known record label the group also owned EMI Music Publishing, which was the largest music publisher in the world. EMI Music Publishing has won the Music Week Award for Publisher of the Year every year for over 10 years; in 2009, for the first time in history the award was shared jointly with Universal Music Publishing. As is often the case in the music industry, the publishing arm and record label are very separate businesses.

As well as the well-known record label the group also owned EMI Music Publishing, which was the largest music publisher in the world. EMI Music Publishing has won the Music Week Award for Publisher of the Year every year for over 10 years; in 2009, for the first time in history the award was shared jointly with Universal Music Publishing. As is often the case in the music industry, the publishing arm and record label are very separate businesses.

EMI administered the publishing rights of over 1.3 million songs; controlling the libraries of artists such as Jay-Z, Beyonce, deadmau5, Timo Maas, Dragon (band), The Prodigy, Megadeth, The Black Eyed Peas, Bloc Party, My Chemical Romance, Avicii, Cannibal Corpse, The Crystal Method, Quarashi, Dragpipe, Avenged Sevenfold, Slipknot (band), MSTRKRFT, and Sean Paul.

EMI's music publishing operations were sold to a consortium led by Sony/ATV Music Publishing in 2012; BMG acquired the music publishing libraries of Virgin Music (which EMI held) and Famous Music UK (which Sony/ATV held).

Wikipedia

Go to stories about the BBC and EMI

Third party photos

Photos below provided to our museum by others

We appreciate all photos sent to our museum. We hope to successfully preserve the sound recording history. If we have not credited a photo, we do not know its origin if it was not taken by the contributor. Please let us know if a photo on our site belongs to you and is not credited. We will be happy to give you credit, or remove it if you so choose.