Sony/Superscope

Superscope

Conceived and designed by the Tushinsky brothers, the "Superscope" wide screen process had its brief heyday from 1954, when Superscope Inc. was incorporated, to 1957.

Conceived and designed by the Tushinsky brothers, the "Superscope" wide screen process had its brief heyday from 1954, when Superscope Inc. was incorporated, to 1957.

It was first used on the film Vera Cruz starring Gary Cooper and Burt Lancaster. Howard Hughes' RKO Pictures used the Superscope process on a total of nine films, including Invasion of the Bodysnatchers. Disney successfully reissued Fantasia in Superscope in the mid-fifties.

In 1957, Superscope's founders, Joseph, Irving, Nathan, and Fred Tushinsky were visiting Japan when they met with the executives of a Japanese electronics company named Sony.

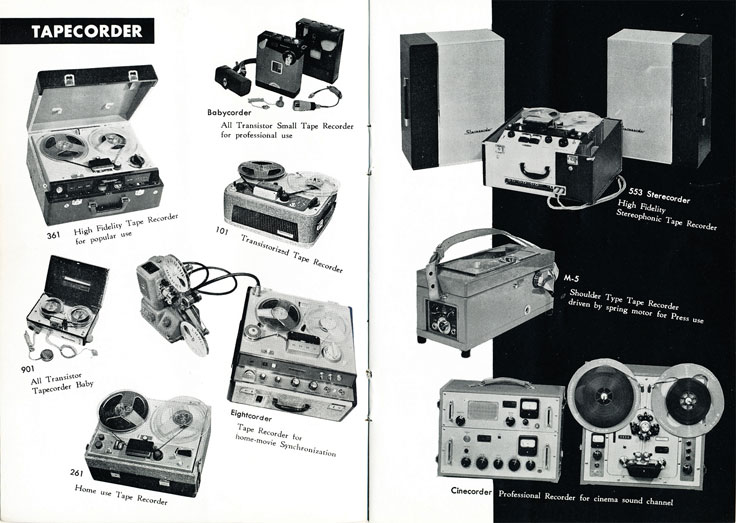

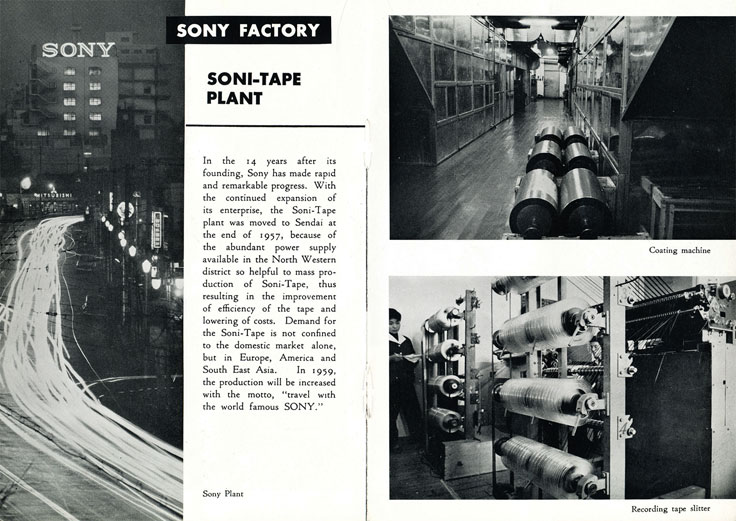

The Tushinsky's discovered that Sony had the world's first stereo tape recorders, with built-in amplifiers.

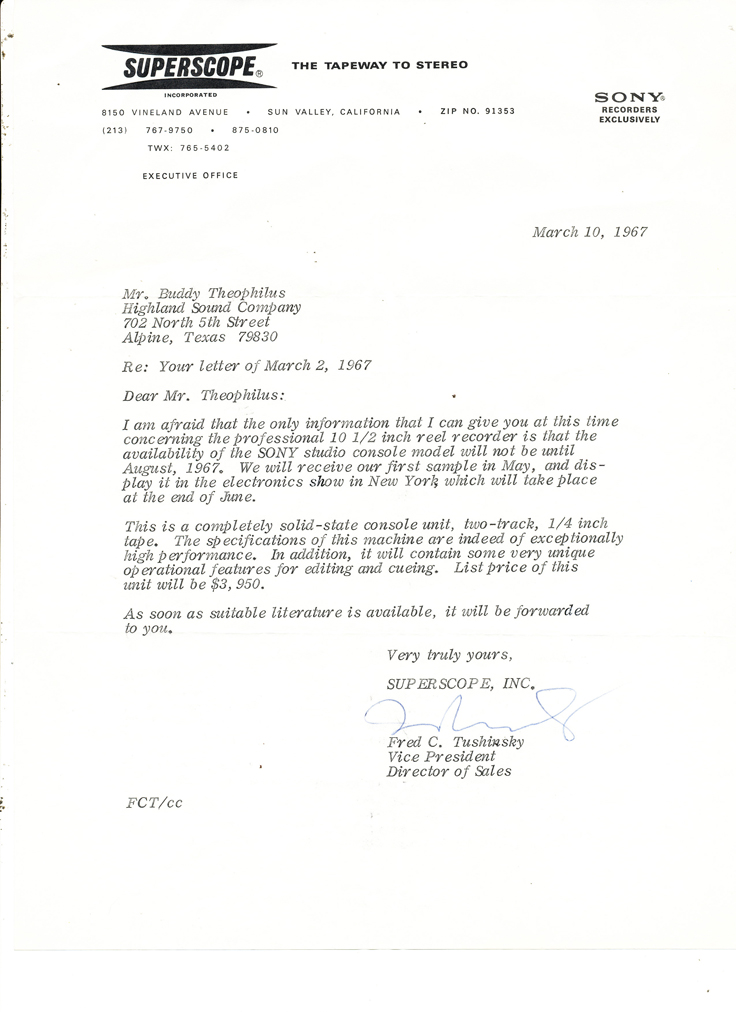

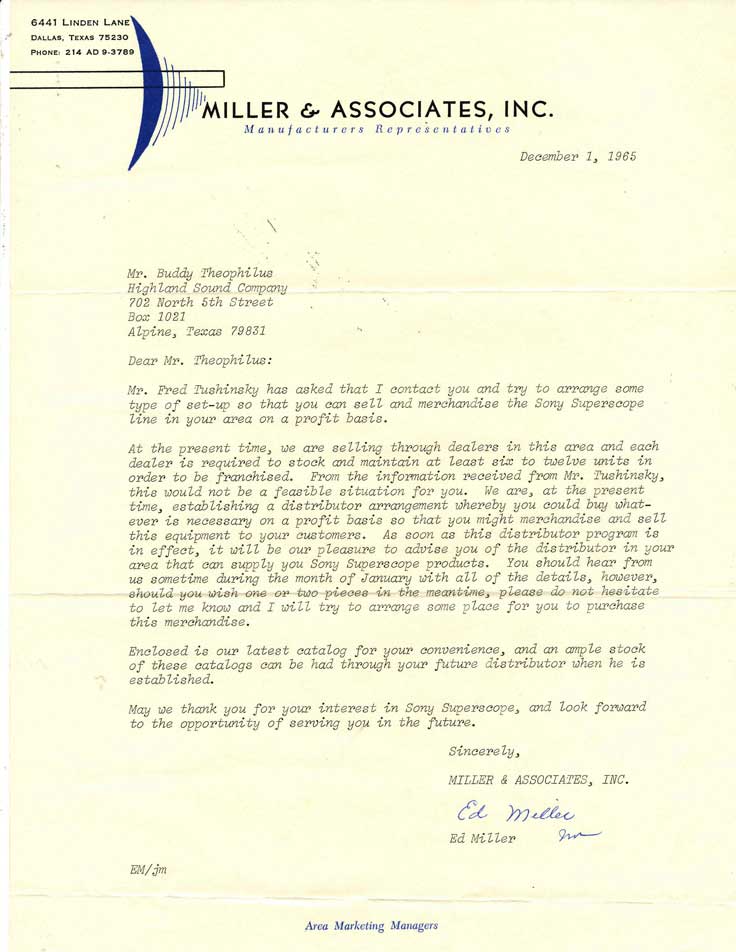

Realizing the potential for the tape recorders for the U.S. market, the Tushinsky's contracted for exclusive rights to distribute them in the United States.

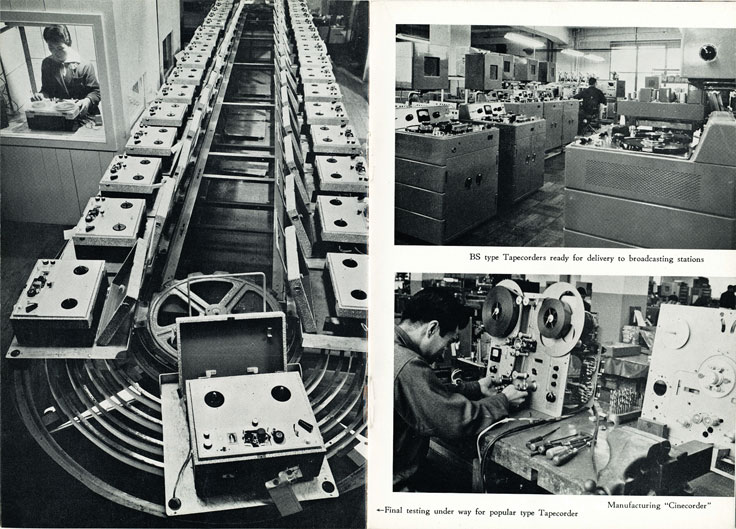

During the 1960's Sony released a variety of Sony/Superscope branded reel-to-reel and cassette tape recorders.

In 1964, Superscope Inc. acquired a small but prestigious hi-fi company from Saul Marantz.

By 1973 Superscope was producing its own line of professional portable cassette recorders.

The Superscope Pianocorder Reproducing System was launched in the late 1970's. It was also available factory-installed in the Marantz Reproducing Piano. The Pianocorder system

The Superscope Pianocorder Reproducing System was launched in the late 1970's. It was also available factory-installed in the Marantz Reproducing Piano. The Pianocorder system  provided a modern alternative to traditional player-piano rolls. It used ordinary cassette tape as a storage medium and played the piano directly from commands stored on the cassette tape.

provided a modern alternative to traditional player-piano rolls. It used ordinary cassette tape as a storage medium and played the piano directly from commands stored on the cassette tape.

Superscope created a fairly extensive library of material for the Pianocorder system, available on over 30 ten-cassette volumes. A large portion of these recordings were made by converting reproducing piano rolls to Pianocorder format. Several famous pianists, including Liberace, George Shearing, and Oscar Peterson, produced recordings directly on Superscope's Bosendorfer concert grand piano.

In 1987, the Pianocorder Division was acquired by Yamaha. Yamaha developed its own competing system and discontinued sales of the digital cassette-driven player piano one month later.

Superscope continued to market and distribute Sony tape recorders exclusively in the United States until January 1, 1975, when Sony acquired back distribution rights to its line of tape recorders from Superscope.

In the 1980s the company sold off many of its assets and changed the name to the Marantz Company.

In 1987 the Marantz Company was purchased by Dynascan Corporation (today's Cobra Electronics).

By 1990, Cobra had sold the Marantz brand to Philips Electronics which negotiated an agreement so that Cobra continued to market Marantz Professional products in the Americas.

In 1993 Superscope Technologies Inc. acquired rights to the Superscope brand and distribution rights to Marantz Professional Products.

It is presently located in Geneva, IL.

History of Sony video • Downloads of Sony 26 minute video available at this link See also Multi-Track recording

Superscope (Sony/Superscope) stories and history - Paul Trethewey

The following information was provided to our Museum by Paul Trethewey who worked for Superscope in the 1970's.

Hi Martin,

Delighted to read you were part of the Superscope [dysfunctional] family just a short while before I was. I would be further delighted to reminisce about details I remember from my days at Superscope. You are welcome to pick and choose anything for your summary.

The story that was handed down to us, as employees, was that the Tushinsky brothers were originally orchestra musicians. Fred played trumpet, Irving played violin, I think maybe Joe played piano, and Nate I don't know. They were somehow connected with the movie industry, perhaps through music, and they did develop an anamorphic, adjustable wide screen lens that was supposed to have competed with Cinemascope. They named their product the Superscope, and as your summary says, Superscope was used on a handful of movies. During the 1950's, the Japanese gained a reputation at building cameras and lenses. The Tushinskys travelled to Japan to find a manufacturer for their special lens. While there, one of their hosts suggested they visit this small company called Sony, who were operating out of an American surplus quonset hut (so the story goes). Sony had developed a cheap reel-to-reel tape recorder -- it might have been their model TC-104 (just guessing) -- and the Tushinskys immediately recognized the sales potential of it. They went about writing a contract with the fledgling company to become their American sales agents. The story goes that Sony told them, "There is no need for a contract. We will stay with you forever!" But, the Tushinskys prevailed and ended up with a 25-year contract to be Sony's marketing arm for tape recorders, tape, microphones, and headphones. And so they did. The tape recorders were sold by "Sony/Superscope."

After the contract expired, Sony showed no loyalty to Superscope, who ironically had pretty much put Sony on the map. I think the Tushinskys suspected this would happen, and they had prepared to fill the vacancy left by Sony with products made by Standard Radio in Japan. These comprised the Superscope audio products, and they were not what you would call professional. They were built to meet a price point -- consumer electronics. By this time, Superscope had bought, for an obscenely low price, the foundering Marantz Company of Woodside, New York. Sol Marantz was a good engineer but a bad businessman. His technically innovative and excellent products were too expensive to manufacture and unprofitable, even though such as the exquisite Marantz 10B FM tuner were groundbreaking feats of engineering. The Marantz name, at the time, was about equal in prestige to McIntosh. And the Tushinskys rode the Marantz reputation, even as they cheapened the products and throttled back the innovation that had gotten Sol Marantz in over his head. They kept the Marantz name and trademark and cachet, but with the exception of a few flagship products designed in Sun Valley, they transferred the engineering of the newer Marantz products to Standard Radio, in Japan, the same outfit that was making the cheap Superscope line of audio products. At some point in about 1975, they re-named Standard Radio "Marantz Japan, Incorporated" or "MJI". The Japanese designs were reviewed by a small team of Marantz engineers in Sun Valley, and later, Northridge, California, but most of the original design work was being done in Japan.

I think their background and love for music might have had a lot to do with their interest in hi-fi and stereo audio. However, they didn't let that stand in the way of making a profit. As the company prospered and the brothers became rich, Joe bought a gigantic Bösendorfer grand piano and had a room in his opulent house remodeled to accommodate the piano plus a device called a "Vorsetzer," which was a type of player piano contraption with mechanical fingers that one could set in front of the piano keyboard and thereby convert a concert grand to a player piano. There were special Vorsetzer piano rolls that ostensibly were made from performances of famous composers and players. After Joe bought his Bösendorfer and Vorsetzer, Irving, not to be outdone, bought the same thing for himself. Irving owned a collection of classic cars. Joe got around in a massive Mercedes Benz 600 limousine. They lived in Encino, a very posh area of the San Fernando Valley northwest of Los Angeles. The Tushinskys were the very picture of nouveau riche.

"Papa Joe" Tushinsky was the CEO of Superscope. Fred was in charge of Marketing and Product Development. Irving was Service. I'm not sure what job Nate had. The only non-family member in the executive suite was Paul Markoff (Markhoff?), who had some family connection to the Hallmark Cards fortune. He was a kind of Chief Financial Officer. All of these men were relentless autocrats and bullies, which, at the time, was expected of successful businessmen.

I started out at Superscope in the service department. Then, because I had some artistic and writing ability, I became involved with a pet project of the national customer service manager, Johnny Robbins, called the Superscope Technical Training Program. We attempted to provide inside information about troubleshooting and repair to our authorized repair technicians around the country -- without admitting that anything ever went wrong with any of the equipment. This made the job virtually impossible. After the Technical Training job, I moved to the Marketing department, where I translated owner's manuals from "Japlish" to English. Finally, I became a Product Manager for some of the Marantz product line -- tape recorders, turntables, and headphones. In this capacity, I was to present my ideas for products to Fred Tushinsky, and if he approved, he would bully Marantz Japan into designing them. Among the products I suggested was a Marantz branded reel-to-reel tape recorder that would be of the same quality and have the same editing features as recording studio tape machines. Unfortunately, this was in 1976, and consumer reel-to-reels were already on the wane. Marantz did have some success with the 5420 cassette recorder and the 6300 turntable, which were products conceived by Jim Murchison, with a little help from me. I also recall having suggested a "component" television that could act as both a TV and a computer screen, which I was told was impossible. Another idea was a turntable whose platter was supported by an air bearing, similar to a frictionless puck. Such was my career as an idea man...

People: I am going to rattle off names of some of the cast of characters at Superscope in the mid-1970's, and maybe you might recognize a name or two. Ready?

Engineering: Flavio Branco, Mario Pinho, Cal Perkins, George Noritake, Ernie Leggett, Dawson Hadley, Pat Hart. Sales: Ken Rottner. Marketing and Product Development: Jim Murchison, Lee Iverson, John McCready, Kathy McDonald, Ron van Meter, Eric Hahn, Reese Hammil, Florence Towers, Gersh Thalberg, Fred Dellar, Rick Jordan. Service: Johnny Robbins, Chuck Jay, Tito Gervasio. Art Dept: Jim Oddie, Rex Irvin, Monique Newman. Worker bees: Marilyn Tallman, Pauline Marynowski, May Lenzer, Deana Bakerink, Ramiro Alcala, Johnny Yamamoto, Fenneke de Witt, Lonny Urbaneak, John Carpenter, Derek Holden, Sherman Wattstein, Linda Davidson, Rhonda Wahl, Susan Asey, Susan Rodriguez.

On Jan 27, 2016, at 7:32 AM, Martin Theophilus wrote:

Thank you Paul! That’s a great history and insight into Superscope. Probably frustrating, but exciting at the same time.

With your permission, I would like to add your summary to the Sony/Superscope page. By any chance do you have any photos from that period?

Once Fred Tushinsky set me up with Balco, I was buffered and never interacted with the main Superscope office again. When I graduated from college, I quit representing Balco (who also had Ampex and all the other major brands). While my degree was in music, and I always kept a part time on-locatoin recording business, I ended up with a career in social work until 1990. Then went full time with our company Phantom Productions.

Have you seen our Marantz page with the prototype high end recorder? Was that the recorder you envisioned?

It's interesting that Robert Metzner (Roberts Recorders) also decided to get exclusive rights from Japan’s Akai for North America, fearing they too would dump him once they got what they needed.

Again, I really appreciate your sharing the stories.

Cheers!

Martin

On Jan 27, 2016, at 4:19 PM, Martin Theophilus wrote:

Thanks for the wonderful information Paul. I really appreciate your sharing it.

Engineering was a wise choice. I was to be a West Texas band director. However, after an exciting experience with 5th grade beginners and that my first teaching contract was to change  from band director to teaching Texas history, I moved on to a higher paying job with the State.

from band director to teaching Texas history, I moved on to a higher paying job with the State.

My college major was trumpet. I never was a dedicated practice person. However, I had a Sony TC-600 which should have been a Sony TC-777, but I couldn’t afford it. The college music department had an Ampex 600 and 620, so that’s what I used to record recitals. I figured they kept me playing trumpet because I always had the stereo Sony recorder beside me to record rehearsals and tours. The TC-600 did okay because I had 2 Shure 556’s and a pair of 30’ telescoping mic stands. The coolest part is that on band tours, I could take the college station wagon with a couple of friends and the recording equipment and travel independently of the bus (also stopping to eat wherever we wanted).

I build a simple recording studio and a couple of custom consoles in my old bedroom at my parents home. One console was supposedly portable for on-location, however it was too heavy to move.

After college, while working in Child Protective Services for the State of Texas, I recorded bands and church choirs in the evening and on weekends. Eventually bought all the Teac gear (A-3340, A-3300-2T, Model 2, etc) which resulted in my producing records for Austin Custom Records around the State. I was briefly ACR’s Chief Engineer, and their studio was probably much more dingy then your old Decca location. Love to see a photo of your console.

I’ll take a closer look at what you’ve written, edit it down some and pass it back to you for review before I add it to the Museum web site.

Cheers!

Martin

January 27, 2016 Paul

The Tushinskys were trend setters, in that they were among the first American businessmen to exploit the Japanese. In the 1950's, Japan was still reeling from its humiliating loss in World War II. Yes, General MacArthur did help them to recover, but by and large, the Japanese economy was devastated, and the Japanese worker and the Japanese engineer could be had for cheap. The Tushinkys, following the Jewish stereotype, recognized a bargain. They were able to squeeze out some very nice work from the Japanese for very little money. The Tushinkys were years ahead of their time in this respect. In the 1960's, the dominant paradigm in American product manufacturing was to do the innovation, design, manufacturing, printing of literature, packaging, marketing, sales, and distribution all domestically: American engineers, American factory workers. The Tushinskys followed a path of doing the market research, describing a product, sending their wish list to Japan, providing a sales channel, and letting the Japanese do the rest. The same is happening today, rampantly, with China. What is different is that in the '60's, there were still American manufacturers.

Yes, it was discouraging and exciting at the same time. Many of us in the Product Development area were pushing for technological innovations. Fred Tushinsky generally resisted those. He was willing to compete on performance specifications, but he preferred to focus on the outward, superficial appearance of the product. I remember a product meeting once with Fred where we were looking at the new offerings from competitor Yamaha. The Yamaha receiver looked like a piece of jewelry, and Fred was determined to out-do Yamaha in that department. This is why, over the years, the Marantz stereo products started to become caricatures of themselves: Glitzy, gratuitous cylindrical aluminum buttons, multiple stylized type fonts on the control panel, "Gyro-Touch Tuning" (which did not work as well as a normal tuning knob), built-in oscilloscopes, and "diamond cut" machining. Customers could be assured that their Marantz product would draw attention to itself, visually as well as audibly.

What was discouraging to me was that Fred waited for innovations from Pioneer, or Yamaha or Kenwood, or anybody else, and then browbeat Marantz Japan into copying their features. Superscope tried to compete with a glitzy looking panel and the Marantz cachet. In many cases, that strategy worked. It is hard to argue with success.

Thanks for sending the link to The Marantz reel to reel prototype. That appeared in 1978, two years after I left Superscope. It is not the same machine that I proposed. Mine was simpler. This machine has the rococo styling that I described above, plus every feature that Fred and his cronies could think of. Dual capstan drive looks like the old Sony 850. Quadraphonic sound. It reminds me of people who have a home designed by an architect, but give him the impossible goal of making the new place look like a composite of every tract home they have ever seen. I do recognize one feature that I pushed for on my design, and that is an LED tape counter that is calibrated in hours, minutes, and seconds, rather than reel rotations.

One more detail I noticed on the photo of the Marantz tape machine you sent the link to: The order of the transport controls. Rewind, Fast Forward, Stop, Play. This is the same as on the Ampex 350. I was advocating this, and it took a lot of talk to convince anyone this was superior to Rewind, Stop, Play, Fast Forward. It has to do with how you shuttle tape when you're editing. A subtle human factors feature. Nice to see they went with it.

Paul

Martin, I was a music major, too, and I also operated a part time on-location recording service. I used my Sony TC651 for this. I had a nice collection of mostly Sony microphones, and I built a mixing console, from scratch, using parts I bought from the Superscope parts department with my 50% employee discount. I still own my console, but I haven't used it in years. Previous to my employment at Superscope, I apprenticed at a sleazy recording studio in Hollywood, in a building that was once Decca Records' studio. It was there I learned about tape deck features that are useful to recording engineers. As far as I was concerned, there was no easier machine to edit tape on than an Ampex 350. I carried that opinion with me when I proposed certain editing features for the reel-to-reel Marantz. This might have been foolish, because the vast majority of consumers had no interest in editing tape, even back in 1976. What I was hoping for was that the proposed Marantz would somehow make its way into the professional or semi-professional recording market, the way that TEAC and Tascam did. I also proposed a Marantz condenser microphone along the lines of the Sony C-37, or more like a Neumann U67. Fred Tushinsky didn't buy that idea, either. He liked the low road, not the high road.

Prior to working at Superscope, I had gone to college for 2 years and then spent 4 years in the Air Force band, marching my way through the Viet Nam Era. As a veteran, I was offered the GI Bill, whereby I could receive a stipend to attend college for 4 years, but the stipend would end 8 years after my discharge. That, along with the realization that I would never, never make my way up the corporate ladder at Superscope, impelled me to quit Superscope and return to college. I changed my major to electrical engineering, a career that promised much better earning potential than being a musician or one of Fred Tushinsky's minions.

I am reminded of another detail: Cigarette smoke. Back in the day, people smoked -- in their offices, in the conference rooms, the cafeteria -- everywhere. The Japanese engineers who visited Superscope in California were notorious chain smokers. I was not a smoker, and for me, to attend product development meetings in a smoke-filled conference room was miserable. Yes, resigning was the right move.

You asked about photos. Recently, I got in touch with one of my old working companions from the Superscope era, Lee Iverson, who was product manager for the Superscope product line. He sent me a few photos taken during that time. I'll try to find those...

Did you major in instrumental music? If so, what did/do you play? I'm a saxophonist.

Paul

About my write-up. You stimulated some neurons, there, but I feel that I was kind of rambling. It was all totally subjective -- not much exists to substantiate my opinions -- but I remember that  period of my life vividly. Perhaps it has something to do with what I recently heard on the radio about a brain chemical called dopamine. You have more of it when you're younger, and it makes for stronger memories and more passionate feelings. It defines when you learn "your music." It was fun remembering the names of the people I worked with 40 years ago. I amazed myself.

period of my life vividly. Perhaps it has something to do with what I recently heard on the radio about a brain chemical called dopamine. You have more of it when you're younger, and it makes for stronger memories and more passionate feelings. It defines when you learn "your music." It was fun remembering the names of the people I worked with 40 years ago. I amazed myself.

My console is borderline too-heavy-to-move, too. I designed it to have 12 input modules, each with phantom power, EQ, two echo sends, a pre-fader cue bus for overdubbing, and stereo solothat reflected the pan pot position. Two more modules provide the echo returns, phonograph amps, test oscillator, talkback/slate, tape monitor, and master level faders. It had 8 regular output channels, each with a lit VU meter. All in a solid walnut console with Brazilian rosewood inlay and a cabretta leather elbow rest! I had intended it to be used with such as a Tascam 80-8. It was a nice design, if I do say so myself. Best of all, it sounded nice. I had a lot of help on the design from my friends in the engineering department! The console was built by a friend who was a woodshop teacher. This project took a year's worth of nights and weekends when I was 26.

mixer.jpeg

I couldn't afford to buy the Tascam 80-8. After a while, the mixer was pressed into service as a "preamp" for my home stereo setup. I would disconnect it and wheel it around on a furniture dolly and load it aboard our 1959 VW microbus to my on-location gigs, usually at the California State University at Northridge, where I was working on my engineering degree. Fond memories!

Paul

My purpose in telling you about the Tushinskys and their Bösendorfer grand pianos and their Teutonic Vorsetzer player piano contraptions was to report that shortly after I quit the company, they developed a product called the “Pianocorder.” It used a cassette deck as the piano roll and did a similar job electronically as the Vorsetzer did pneumatically. I imagine that, for Joe Tushinsky, this was a labor of love, an indulgence, because it was not a big revenue generator.

Paul